(publication update: I have a hiking story for kids in the April issue of Spider. The story is also mentioned, and I’m interviewed!, in this article here. I’ll have a few new stories coming out soon in Cicada, Gulf Coast, and The Southern Review. Stay tuned.)

(reading update: rereading The Power (Naomi Alderman), it is just as gripping the second time around; reading the Denis Johnson collection The Largesse of the Sea Maiden; and I’m wondering if this time is the time I am going to finish reading or even get half way through Karl Ove Knausgard’s My Struggle. I have read the beginning maybe 4 times but always get sidetracked. I really love the beginning.)

The Invention of Nature (by Andrea Wulf) has to be one of my favorite non-fiction books ever. It reads as part adventure tale, part travelogue, part explorer journal, part science history, part environmental awakening. Also, it’s stunningly written. For example: “One night, as the rain fell in torrents, Humboldt lay in his hammock fastened to palm trees in the jungle. The lianas and climbing plants formed a protective shield high above him. He looked up into what seemed like a natural trellis decorated with the long dangling orange blossoms of heliconias and other strangely shaped flowers. Their campfire lit up this natural vault, the light of the flames licking the palm trunks up to sixty feet high. The blossoms whirled in and out of these flickering illuminations, while the white smoke of the fire spiralled into the sky which remained invisible behind the foliage.” I can read and reread that passage and never tire of it.

The Invention of Nature (by Andrea Wulf) has to be one of my favorite non-fiction books ever. It reads as part adventure tale, part travelogue, part explorer journal, part science history, part environmental awakening. Also, it’s stunningly written. For example: “One night, as the rain fell in torrents, Humboldt lay in his hammock fastened to palm trees in the jungle. The lianas and climbing plants formed a protective shield high above him. He looked up into what seemed like a natural trellis decorated with the long dangling orange blossoms of heliconias and other strangely shaped flowers. Their campfire lit up this natural vault, the light of the flames licking the palm trunks up to sixty feet high. The blossoms whirled in and out of these flickering illuminations, while the white smoke of the fire spiralled into the sky which remained invisible behind the foliage.” I can read and reread that passage and never tire of it.

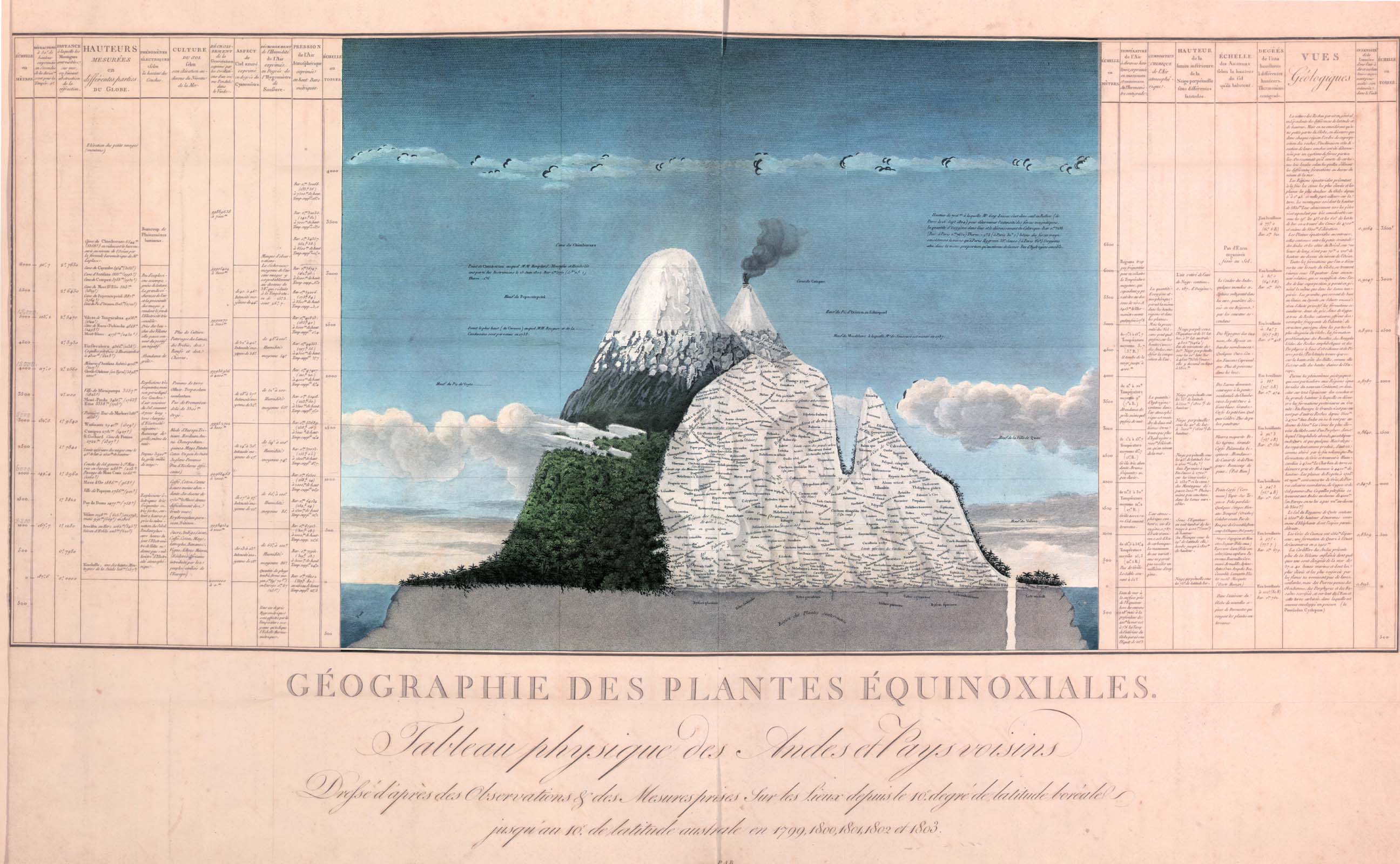

The book both gives me hope in humanity and also makes me very sad. It appears we’ve known, or at least some people have known, for hundreds of years how humans are negatively impacting the planet in the name of progress. Humboldt observed in 1800: “When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters, with an imprudent precipitation, the springs are entirely dried up, or become less abundant. The beds of the rivers, remaining dry during a part of the year, are converted into torrents, whenever great rains fall on the heights. The sward and moss disappearing with the brush-wood from the sides of the mountains, the waters falling in rain are no longer impeded in their course: and instead of slowly augmenting the level of the rivers by progressive filtrations, they furrow during heavy showers the sides of the hills, bear down the loosened soil, and form those sudden inundations, that devastate the country.” Or in 1854, “Haeckel wrote that the ancients had felled the forests in the Middle East which in turn had changed the climate there. Civilization and the destruction of forests came ‘hand in hand’, he said. Over time it would be the same in Europe, Haeckel predicted. Barren soils, climate change and starvation would eventually lead to a mass exodus from Europe to more fertile lands. ‘Europe and its hyper-civilisation will soon be over,’ he said.” There are countless examples like these throughout the book Yet we have continued and still continue to, you know, ruin the world.

But here’s the hopeful part: the fact that people such as Humboldt and his intellectual descendants–Henry David Thoreau, Charles Darwin, George Perkins Marsh, Ernest Haeckel, and John Muir–have existed, and their beautiful brains have managed to provide us with a different way of thinking about the world and our relationship to the world, where everything, ourselves included, is interconnected. So maybe this can happen again, and someone, or more likely a group of people, can rethink our relationship to everything, and help us see the world and each other in a new light. (“‘Why ought man to value himself as more than an infinitely small unit of the one great unit of creation?’ Muir asked. ‘The cosmos,’ he said, using Humboldt’s term, would be incomplete without man but also without ‘the smallest transmicroscopic creature’.”).

Here’s how The Invention of Nature begins:

“THEY WERE CRAWLING on hands and knees along a high narrow ridge that was in places only two inches wide. The path, if you could call it that, was layered with sand and loose stones that shifted whenever touched. Down to the left was a steep cliff encrusted with ice that glinted when the sun broke through the thick clouds. The view to the right, with a 1,000-foot drop, wasn’t much better. Here the dark, almost perpendicular walls were covered with rocks that protruded like knife blades.

Alexander von Humboldt and his three companions moved in single file, slowly inching forward. Without proper equipment or appropriate clothes, this was a dangerous climb. The icy wind had numbed their hands and feet, melted snow had soaked their thin shoes and ice crystals clung to their hair and beards. At 17,000 feet above sea level, they struggled to breathe in the thin air. As they proceeded, the jagged rocks shredded the soles of their shoes, and their feet began to bleed.”

I mean, wow. I read that passage out loud to my husband, and then proceeded to read quite a lot of the book out loud to him–it’s a book of breathtaking details and surprising revelations that you must share with somebody.

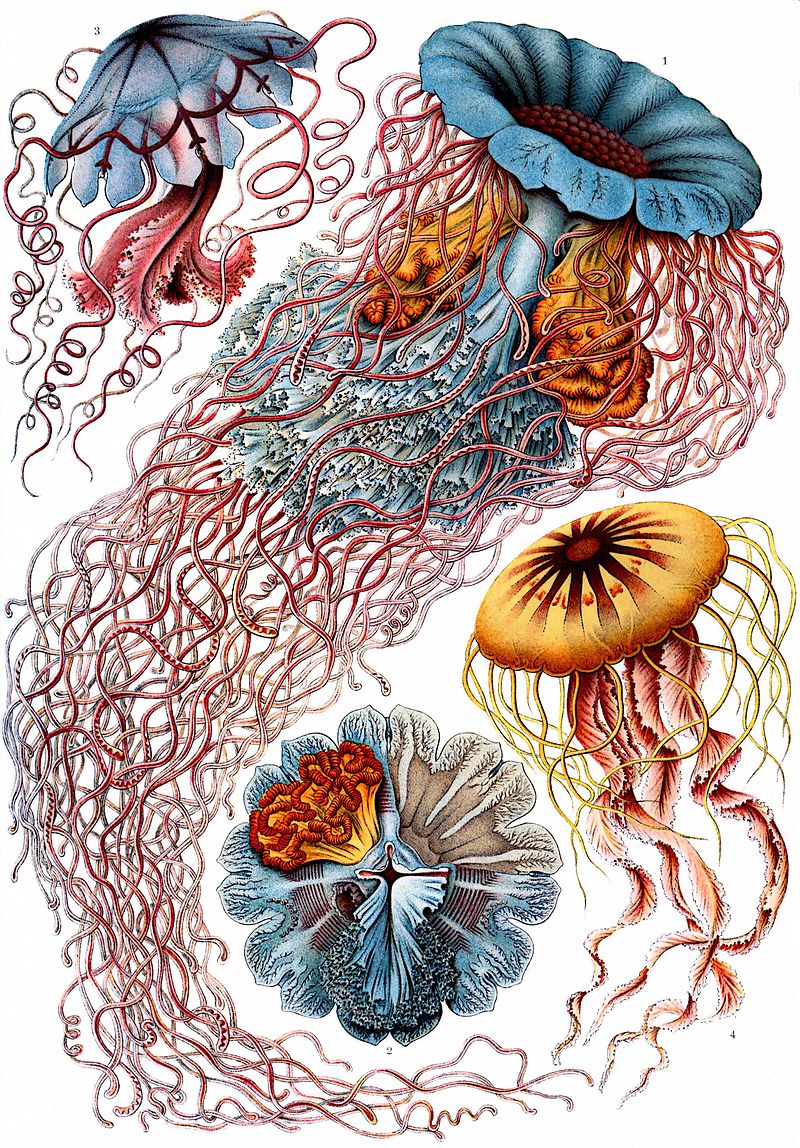

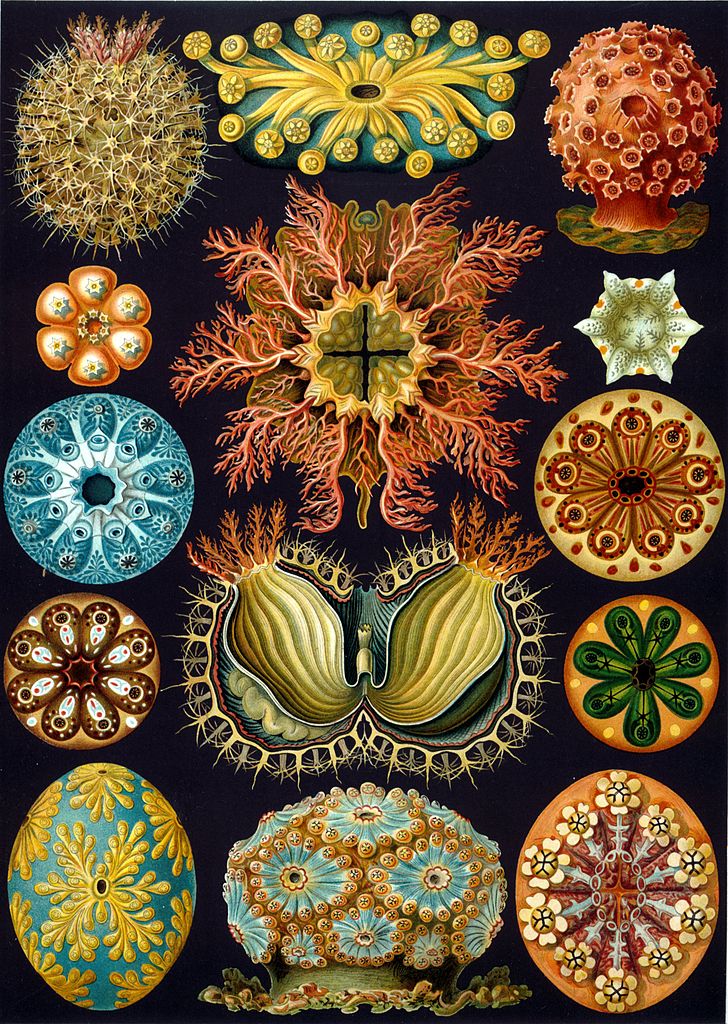

I fell in love with Humboldt, of course, by the end, though I imagine or rather I know he would be irritated with any of my affections. Actually I fell in love with, well, all the scientists and environmentalists in the book. More specifically, I fell in love with Ernst Haeckel’s drawings. He became a scientist first, an artist second, and he was self-taught, so when I googled his illustrations, I was not expecting this.

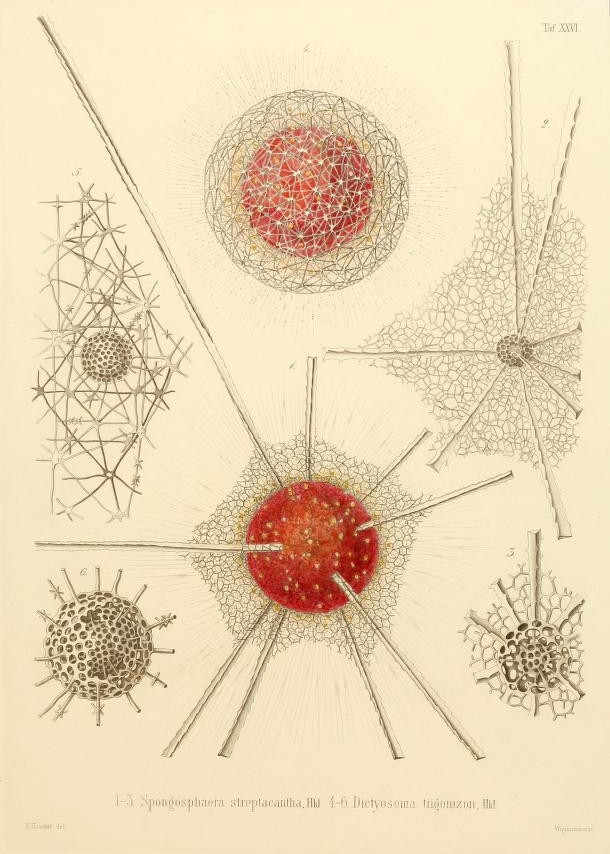

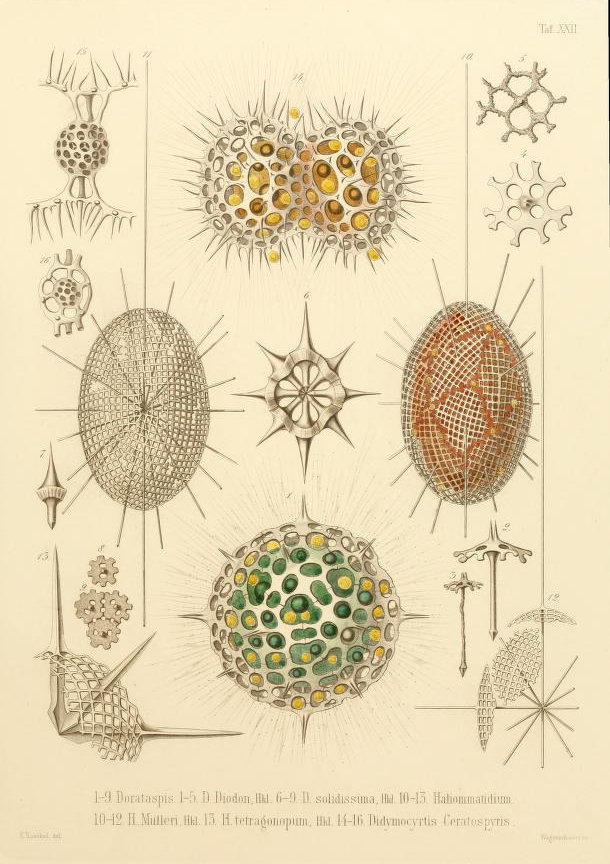

Those are jellyfish. And here are some of the microscopic organisms he drew, sometimes with one eye pressed to the microscope, the other eye focused on his drawings.

These drawings to me demonstrate how amazing the natural world is, even the microscopic world. And in doing so, it reminds me of the enormous loss that occurs when any species goes extinct. Really, how could humans compete with this sort of beauty? In the very least, we should realize the jellyfish and the radiolaria are our equals. I could probably spend the entire day posting Haeckel’s drawings, but I will show some restraint, and instead refer you to this excellent article on The Public Domain Review. And this article too. And, okay, just one more Haeckel drawing.

Beautiful beautiful beautiful! Thank you for introducing me to this wonderful book – and those DRAWINGS! Can’t get them out of my head.