Stella of late has become enamored with all the Disney versions of the fairy tales. This is rather painful for me, so for her 5th birthday, I wanted to get her a copy of “real” Pinocchio but an illustrated version. I have such fond memories of reading Jasper the original Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi when he Stella’s age. Sure, the book is dark and more than a little creepy (Pinocchio smashes the cricket of conscience, for instance, early on, and at one point the little wooden boy is hung from a tree by a noose), but I also remember it being wildly beautiful, surreal, complex, and fun. Honestly I can’t find which translation of the book Jasper and I read–it was just a random one from the library, and I guess we had good luck.

For Stella’s birthday, I made a very bad decision and went with the Candlewick Illustrated Classics. Not only are the collages by Sara Fanelli rather odd, at least to a 5-year-old’s eyes, but the translation by Emma Rose is less than ideal (also a sans serif for a font choice for a 19th story? Save me!). Stella was fidgety while I was reading it to her, as was I, and I wondered if I had imagined the goodness of this book. She asked to stop reading a few chapters in.

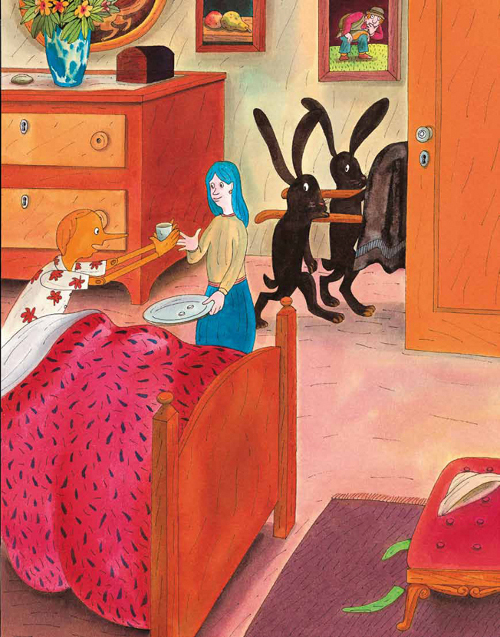

But I wasn’t ready to give up on Pinocchio quite yet. So I ordered another version, this one illustrated by the Italian artist Fulvio Testa and translated by poet Geoffrey Brock (who has also done translations of Umberto Eco’s work). What a difference a good translation makes (and good illustrations too!).

But I wasn’t ready to give up on Pinocchio quite yet. So I ordered another version, this one illustrated by the Italian artist Fulvio Testa and translated by poet Geoffrey Brock (who has also done translations of Umberto Eco’s work). What a difference a good translation makes (and good illustrations too!).

Honestly I still don’t know if this will be Stella’s favorite book – she’s kind of fallen in love with the more innocent Pinocchio from Disney, and she hated that the “real” Pinocchio killed the cricket, even if by accident. I think there may be too much cruelness in the book for her right now.

But I’m enjoying the Brock translation. It’s fascinating how subtle word choice can ruin, or elevate, a story, and I’m hoping it will teach my something about sentence revision.

Here are a few comparisons–the first version is the Rose translation, the second the much stronger Brock translation.

- “He was delighted” versus “He cheered right up.”

- The flattening that happens when cliches are used: “And then, quick as a flash, he picked up his ax to strip the bark and whittle the wood down” versus “Wasting no time, he picked up his sharp hatchet to start removing the log’s bark and trimming it down…”

- Or having Mr. Cherry swearing that he heard a voice — “He could have sworn he’d heard a voice–a thin little voice–exclaim ‘Please don’t hit hard.’” versus having him actually hear a voice (“because a heard a little high-pitched voice pleading, ‘Don’t hit me too hard!’”).

- Or “You can imagine how amazed Mr. Cherry was” — so flat!–versus the subtly different “Just imagine dear old Master Cherry’s reaction!”

- Or “No, that’s ridiculous.” versus “I can’t believe that.” Much more effective to have the I present in the sentence and that word “believe” is full of a power that “ridiculous” lacks.

- Or “He picked up the ax again and gave the piece of wood a good whack.” versus “And picking the hatchet back up, he dealt the piece of wood a heavy blow” (I think it’s the useless adjective “good” that bothers me there).

- Or “‘Ouch!’ yelped the same little voice. ‘That hurt!” versus “‘Ouch! You hurt me!’ cried the same little voice, bitterly.” What richness that adverb “bitterly” adds.

- Or see how grammar helps the flow of the sentence. The first uses short choppy sentences that feel awkward and seem to accentuate the cliched, over the top description. “This time Mr. Cherry was left speechless. His eyes bulged out of their sockets. His mouth gaped open. His tongue hung down his chin. He looked like one of those stone faces you may have seen on water fountains.” But look what a colon can do: “This time Master Cherry was struck dumb: his eyes bugged out of his head in fright, his mouth gaped, his tongue dangled down to his chin, like those grotesque faces carved on fountains. “

Here’s the first few paragraphs of each translation so you can compare yourself.

Candlewick Illustrated Classics version

Once upon a time there was…

“A king?” did I hear you cry?

But if you did cry “king,” children, you were wrong. Because once upon a time there was….

…a piece of wood.

It wasn’t a piece of fine mahogany. It was an ordinary log, just like the logs you burn in your fireplace to warm your toes in winter.

Now, one day this piece of wood ended up–don’t ask me how–in the workshop of an old carpenter whose name was Antonio–although, on account of the tip of his nose always being red and shiny, everybody knew him as Mr. Cherry.

When Mr. Cheery saw our ordinary piece of wood, he was delighted.

“Perfect timing,” he muttered, rubbing his hands together with satisfaction. “It’s just what I needed to make that table leg.” And then, quick as a flash, he picked up his ax to strip the bark and whittle the wood down. But just as he was about to make that first cut, he froze with his arm midair. He could have sworn he’d heard a voice–a thin little voice–exclaim “Please don’t hit hard.”

You can imagine how amazed Mr. Cherry was.

He cast puzzled looks around the room, trying to discover where the little voice might have come from, but saw nobody. He looked under his workbench. Nobody. He peered into the cupboard he always kept locked. Nobody. He rummaged around in teh bin he used to store sawdust and wood chips. Nobody. He even opened the door of his workshop to glance down the street. Still nobody. What was going on?

“Oh, well,” he said at last, with a laugh and a scratch of his wig. “I must have imagined it. Back to work.”

He picked up the ax again and gave the piece of wood a good whack.

“Ouch!” yelped the same little voice. “That hurt!”

This time Mr. Cherry was left speechless. His eyes bulged out of their sockets. His mouth gaped open. His tongue hung down his chin. He looked like one of those stone faces you may have seen on water fountains. As soon as he got his voice back, he began talking to himself, shaking and stammering with fear. “Where on earth did that voice come from? There’s nobody here but me. Could it have been this piece of wood? Could it have learned to talk and cry like a child? No, that’s ridiculous. Let’s have a look at it,” said Mr. Cheery. “It’s a perfectly ordinary kind of log. It’s the kind of log that would bring your pot of beans to boil if you threw it on the fire.” Mr. Cherry thought for a moment. “Is there someone hiding inside it? They’d better not be! I’ll fix them!”

The Geoffrey Brock translation, which I do recommend

Once upon a time there was . . .

“A king!” my little readers will say at once.

No, children, you’re wrong. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood.

It wasn’t a fancy piece of wood, just a regular woodpile log, the kind you might put in your stove or fireplace to stoke a fire and heat your room.

I don’t know how it happened, but the fact is that one fine day this piece of wood turned up in the workshop of an old carpenter, Master Antonio by name, though everyone called him Master Cherry, on account of the tip of his nose, which was always shiny and purple, like a ripe cherry.

As soon as Master Cherry saw that piece of wood, he cheered right up. He rubbed his hands together with satisfaction and mumbled in a soft voice, “This log has turned up at a good moment. I think I’ll use it to make me a table leg.”

Wasting no time, he picked up his sharp hatchet to start removing the log’s bark and trimming it down, but just as he was about to strike the first blow, his arm froze in midair, because he heard a little high-pitched voice pleading, “Don’t hit me too hard!”

Just imagine dear old Master Cherry’s reaction!

His bewildered eyes roamed the room to see where on earth that little voice had come from, but he didn’t see anyone! He looked under his workbench — nobody there. He looked inside a cabinet he always kept shut — nobody there. He looked in his basket of wood shavings and sawdust — nobody there. He even opened his workshop door to take a look in the street — nobody there. So what was going on?

“I see,” he said then, laughing and scratching his wig. “Clearly I must have imagined that little voice myself. Now let’s get back to work.”

And picking the hatchet back up, he dealt the piece of wood a heavy blow.

“Ouch! You hurt me!” cried the same little voice, bitterly.

This time Master Cherry was struck dumb: his eyes bugged out of his head in fright, his mouth gaped, his tongue dangled down to his chin, like those grotesque faces carved on fountains. When he regained the use of speech, he said, trembling and stammering with fear, “That little voice that said ouch, where could it have come from? Because there’s not a living soul in this place. Could this piece of wood have somehow learned to cry and complain like a little boy? I can’t believe that. Look at this log — it’s a piece of firewood, like any other. If I threw it on the fire I could bring a pot of beans to a boil. So what’s going on? Could someone be hidden inside it? If anyone’s hiding in there, tough luck for him. I’ll show him what’s what!”

THANKS!

This was a great help. I’ve read about Geoffrey Brock’s translation, however you provided me with some great examples!