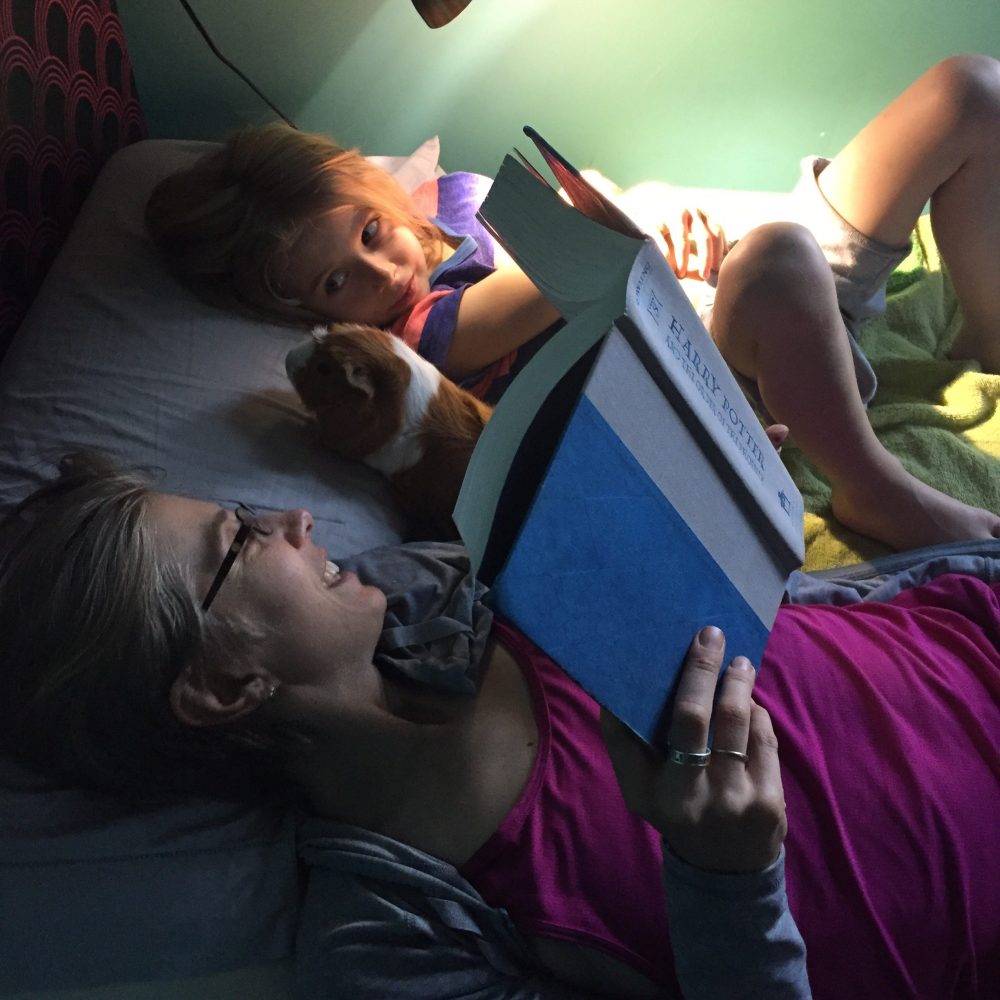

(Side note: new speculative story for teens out in the November/December issue of Cicada magazine! Also there’s an interview with me. Also, perhaps most excitingly, there is my favorite author photo in that issue: me lying in my daughter’s bed, along with my daughter, her classroom guinea pig, and a Harry Potter book. It’s not the most flattering picture (of me, anyway, the guinea pig and my daughter look great) but, you know what, that was a moment of transcendental happiness for me. I loved that guinea pig. I loved my daughter. I loved Harry Potter. I loved my daughter’s bed. I loved reading to that guinea pig. I loved how, when reading, the guinea pig would look up from his carrot then slowly, slowly creep toward me, closer and closer, until its front paws were on my shoulder, and its face was sniffing my face, like he was trying to find the words I was speaking out loud. Other times, he would try and eat the book. He was my ideal reader and I miss him.)

(I also have a new story, “Safe,” in the Fall issue (65:3) of Epoch, a journal I had been sending stuff to for the past 11 years, so this is particularly nice for me. It’s a story told by an evangelical narrator who is relatively new to the faith. I wrote it to help me understand my little sister, who got re-baptized into an evangelical church 2 or 3 years ago.)

Anyway, these days, I’m trying to find a way to write about my life in a way that doesn’t bore me and also doesn’t feel like I’m selling off my children. I tried a few straight forward essays, but putting my son’s actual name into one of those pieces made me sick to my stomach. I hated the thought that I was presenting my version of my son’s life as this fact, this truth, while his version of the story remained untold. Also I felt very constrained by the truth. So that was the end of my straight-forward essay career. A better fit, perhaps, is the “hermit crab” essay (nice essay on what this means here) – essentially it’s using form to examine/ponder something about one’s life. A truth within a form. A great example of a hermit crab essay: The Pain Scale, by Eula Biss – it’s as powerful, and fascinating, and readable to me as any piece of fiction. But I love that it’s also true. And I love that it doesn’t have to tell a narrative or story. I’m also interested in the idea of “speculative non-fiction,” where you take elements of your life, and insert speculative elements, and then write about it.

I’m slowly reading Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle (still on volume 1!). I love how it’s not his life specifically that makes the book so mesmerizing, but the fact that meaning can be found in the smallest details of a life. That every life, every detail, can be meaningful. And the writing is kick-ass too. Actually, I find myself unable to read it most days/nights, because it requires so much energy. I get overly preoccupied with figuring out what I can learn from every sentence and, in the process, I end up taking way too many notes. Still, I think there’s something very essential that can be learned about writing creative non-fiction from this book. I’d love to see what a female version of this sort of writing looks like.

Bluets (Maggie Nelson) is another form of creative non-fiction that intrigues me. I’ll admit, when I first bought the book, I read a few of the numbered sections and put it down. It felt so precious, so performed, for my tastes anyway, the voice too heightened, and there are so many paler imitations of this structure out there. The heart of the book felt like, in many moments, it was at the mercy of the writing. That said – once I got past the first few pages, there are still so many lovely, moving parts. The transitions, the organizational structure, the flow, is pretty mind-blowing. While I wish Nelson would take it down a few steps, and be a little more grounded, it’s also clear that isn’t what she was trying to do. Her voice feels like that of a questioning, seeking oracle, and I get that it’s not meant to be straight creative-non fiction. Maybe it’s more poetry. Anyway, I’m glad I read it. Here’s a passage I particularly loved about depression, which I’ve been trying to find a way to write about, so it’s always this exciting huge deal when I find an example of someone doing it successfully. How do you write about your own sadness without getting self-indulgent and boring people? That’s what I’m trying to figure out. From Bluets:

“127. Ask yourself: what is the color of a jacaranda tree in bloom? You once described it to me as “a type of blue.” I did not know then if I agreed, for I had not yet seen the tree.

128. When you first told me about the jacarandas I felt hopeful. Then, the first time I saw them myself, I felt despair. The next season, I felt despair again. And so we arrive at one instance, and then another, upon which blue delivered a measure of despair. But truth be told: I saw them as purple.

129. I don’t know how the jacarandas will make me feel next year. I don’t know if I will be alive to see them, or if I will be here to see them, or if I will ever be able to see them as blue, even as a type of blue.

130. We cannot read the darkness. We cannot read it. It is a form of madness, albeit a common one, that we try.

131. “I just don’t feel like you’re trying hard enough,” one friend says to me. How can I tell her that not trying has become the whole point, the whole plan?

132. That is to say: I have been trying to go limp in the face of my heartache, as another friend says he does in the face of his anxiety. Think of it as an act of civil disobedience, he says. Let the police peel you up.

133. I have been trying to place myself in a land of great sunshine, and abandon my will therewith.

134. It calms me to think of blue as the color of death. I have long imagined death’s approach as the swell of a wave—a towering wall of blue. You will drown, the world tells me, has always told me. You will descend into a blue underworld, blue with hungry ghosts, Krishna blue, the blue faces of the ones you loved. They all drowned, too. To take a breath of water: does the thought panic or excite you? If you are in love with red then you slit or shoot. If you are in love with blue you fill your pouch with stones good for sucking and head down to the river. Any river will do.

135. Of course one can have “the blues” and stay alive, at least for a time. “Productive,” even (the perennial consolation!). See, for example, “Lady Sings the Blues”: “She’s got them bad / She feels so sad / Wants the world to know / Just what her blues is all about.” Nonetheless, as Billie Holiday knew, it remains the case that to see blue in deeper and deeper saturation is eventually to move toward darkness.

136. “Drinking when you are depressed is like throwing kerosene on a fire,” I read in another self-help book at the bookstore. What depression ever felt like a fire? I think, shoving the book back on the shelf.

137. It is unclear what Holiday means, exactly, when she sings, “But now the world will know/She’s never gonna sing ’em no more/No more.” What is unclear: whether she is moving on, shutting up, or going to die. Also unclear: the source of her triumphance.

138. But perhaps there is no real mystery here at all. “Life is usually stronger than people’s love for it” (Adam Phillips): this is what Holiday’s voice makes audible. To hear it is to understand why suicide is both so easy and so difficult: to commit it one has to stamp out this native triumphance, either by training oneself, over time, to dehabilitate or disbelieve it (drugs help here), or by force of ambush.

I just read your short story “Two Moons” in the Sun, and then re-read it twice. It’s such a good story, and I’m looking forward to reading more of your work.

Jane Becker

Santa Cruz, CA